Peter Carruthers

This is the third in my series on, ‘What is church?’. The plan for the series is, primarily, to offer tasters of the teachings of some past and present theologians. In the previous two articles, drawing on the thinking of Stanley Hauerwas and Lesslie Newbigin, we saw, respectively, how the church is meant to be a ‘disciplined community’ and a ‘sign, instrument and foretaste’ of God's redeeming grace for the whole life of society.

Both Hauerwas and Newbigin seek to reflect or interpret aspects of NT ecclesiology. In this article, I head right back to the beginning and offer some insights from Paul himself (who wrote 13 of the 27 books of the NT) on what makes a church a church.

Planting and strengthening the churches

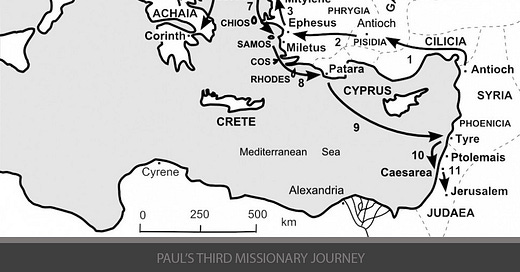

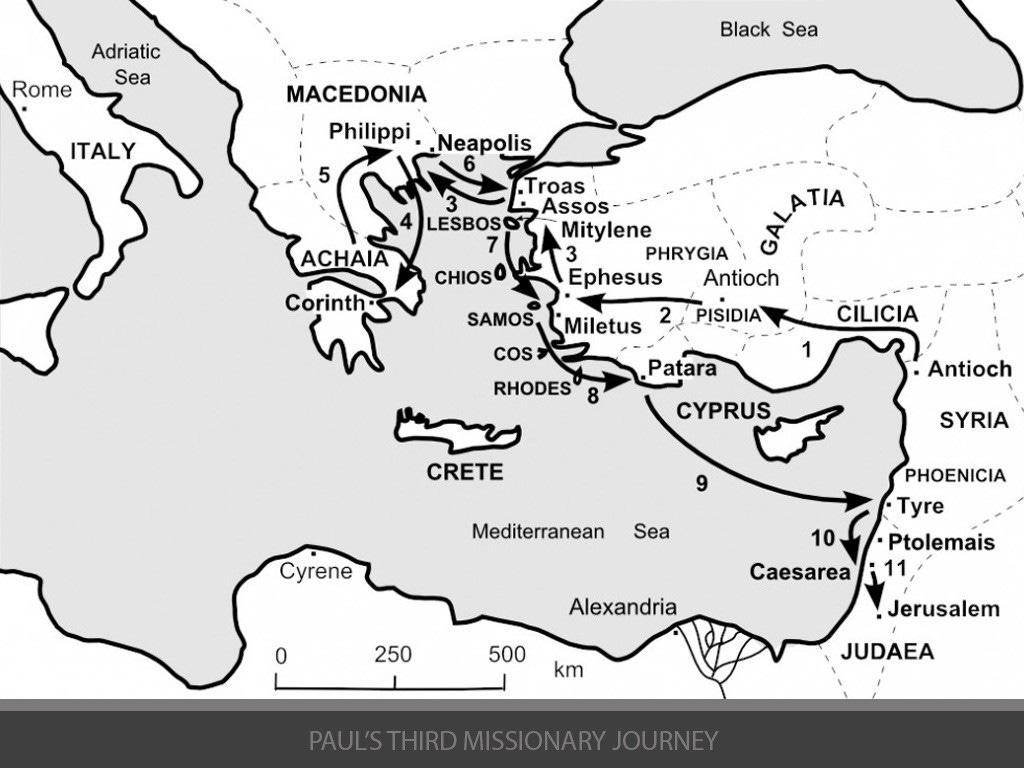

In much of the latter part of Acts, we see Paul and his co-workers first planting churches and then returning to strengthen them (eg Acts 15:36-41), so that they both deepened in faith and increased in numbers. Their aim was to be faithful to Jesus’ command to “make disciples of all nations”, to the ‘Great Commission’ (Matthew 28:16-20).

Planting and strengthening churches was central to their understanding of, and strategy to carry out, Jesus’ command. Jesus builds His Church (Matthew 16:18). But it is the task of His apostles, prophets, pastors, teachers and evangelists to extend, equip and edify it (Ephesians 4:7-16).

Christendom and post-Christendom

Centuries of Christendom makes applying NT ecclesiology difficult. Different Christian churches, denominations and theologians have different understandings of Christendom, what it means, and why the Lord ordained or allowed it. But that is for another time.

Yet now, our post-Christian Western world looks a lot more like the world of the NT than it has for most of Christian history. Maybe this makes ‘rethinking’ church and applying NT ecclesiology a little easier?

Authentic church

What then, according to Paul, are some of the marks of authentic church? And how do we strengthen church so that it is more authentic? Below, I suggest five things that reflect the key characteristics of authentic, mature church and that represent targets for attention if a church is to be made strong. There are, of course, more.

Order

Churches are meant to be ordered and orderly, and strengthening a church means setting “in order the things that are lacking” (Titus 1:5), in terms of leadership and ministry. Paul urged Titus to “appoint elders in every town” (Titus 1:5) and explained to the Ephesians that, as above, the church grows to maturity and is equipped for service through the ministry of apostles, prophets, evangelists and pastors-teachers (Ephesians 4:7-16). Paul also has much to say about church discipline, an aspect of church life that runs right against our current culture!

Conduct

Paul also has a great deal to say about how we should live and especially how we should conduct ourselves in the “household of faith” (Galatians 6:10) and as “God's chosen ones” (Colossians 3:12-14). The distinguishing mark of Jesus’s disciples is, after all, that we love one another (John 13:35).

Doctrine

A third mark of authentic and mature church is a concern for “sound doctrine” (Titus 2:1). The new church of Acts 2, “devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching” (Acts 2:42). Paul urged the Thessalonians to “stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15).

This is, I believe, an absolutely critical issue for us now, but not necessarily a popular one. In the not-so-distant past, there was perhaps a fairly simple division between ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ understandings of Scripture. But now, the whole church scene is much more complex and fragmented, reflecting the wider culture.

Deception has always been a possibility, and we are warned that it will become more so in the “latter times” (1 Timothy 4:1). In such times, it is essential to ‘underpin’ our (biblical) foundations.

Fellowship

The early church also “devoted themselves to fellowship” (Acts 2:42), to sharing meals with one another “from house to house” (Acts 2:46) and even to a shared economy (Acts 4:32).

As this writer notes, Paul’s prayer for the Philippians (1:3-11) sets out five strands of true fellowship in Christ: praying for one another (1:3,4); serving God together (1:5,7); trusting that God is working in each other and will complete His work (1:6); partaking together in God’s grace (1:7), and; having heartfelt affection for one another (1:8).

Deepening fellowship is not just an imperative at all times, but also a specific response to our present times (Hebrews 10:25). And, at present, this will need to be worked out within and/or outside institutional affiliations.

Fellowship is not a cup of tea after a church service, nor a club or common interest group, but a shared life of worship, prayer, loving relationships, ‘doing good’ to one another in the ‘household of faith’ (Galatians 6:10), learning together, and service of others.

Ultimately fellowship is ‘of the Holy Spirit’ (2 Corinthians 13:14) as we affirm every time we share in the Grace. The church is the community of the Spirit and our fellowship is with the Lord and with believers present and with the great cloud of witnesses of those who have gone before.

Mission

Finally, in Paul’s understanding, strengthening church means strengthening mission. Paul and his co-workers were sent out to plant and strengthen churches, which themselves also sent out workers to do the same. Authentic churches proclaim the Gospel and make disciples.

As Kevin de Young describes, Acts 14:21-23 “presents us with the three-legged stool of the church’s mission. Through the missionary work of the Apostle Paul, the early church aimed for:

New converts: ‘when they had preached the gospel to that city and had made many disciples’ (v 21);

New communities: ‘And when they had appointed elders for them in every church’ (v 23);

Nurtured churches: ‘strengthening the souls of the disciples, encouraging them to continue in the faith’ (v 22).”

As de Young continues, “evangelism, discipleship, church planting - that’s what the church in Antioch sent Paul and Barnabas to do, and these should be the goals of all mission work”. “Strictly speaking”, he writes, “the church is not sent out, but sends out workers from her midst”.

Contemporary Christian missiology has added social, political and environmental dimensions to its understanding of the Church’s mission, ie the Church’s task is both to ‘populate heaven’ and ‘change the world’. For example, the ‘five marks of mission’ adopted by the General Synod of the Church of England in 1996 are as follows.

To proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom.

To teach, baptise and nurture new believers.

To respond to human need by loving service.

To seek to transform unjust structures of society, to challenge violence of every kind and to pursue peace and reconciliation.

To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth.

Nevertheless, the core of the Church’s mission remains the ‘Great Commission’, a version of which occurs in all four gospels and Acts (Matthew 28:16-20; Mark 13:10; 14:9; Luke 24:44-49; John 20:21; Acts 1:8). This, as de Young concludes, was at the heart of Paul’s understanding of mission and, indeed, of the purpose of the church.

“We see over and over in Paul’s missionary journeys, and again in his letters, that the central work to which he has been called was the verbal proclamation of Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord (Romans 10:14-17; 15:18; 1 Corinthians 15:1-2,11; Colossians 1:28)…… His goal as a missionary was the conversion of Jews and pagans, the transformation of their hearts and minds, and the incorporation of these new believers into a mature, duly constituted church. What Paul aimed to accomplish as a missionary in the first century is an apt description of the mission of the church for every century.”1

“From Jerusalem and all the way around to Illyricum I have fulfilled the ministry of the gospel of Christ; and thus I make it my ambition to preach the gospel, not where Christ has already been named, lest I build on someone else's foundation, but as it is written, ‘Those who have never been told of him will see, and those who have never heard will understand’”. (Romans 15:19-21).

“And Jesus came and said to them, ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age’”. (Matthew 28:18-20).

De Young does not dismiss ‘cultural transformation’, but sees it has a spin-off or by-product of preaching the Gospel and making disciples: “the mission given to the bumbling band of disciples was not one of cultural transformation - though that would often come as a result of their message”. He is critical of John Stott’s “arguing for social action as an equal partner of evangelism” and of Stott’s suggestion that “we give the Great Commission too prominent a place in our Christian thinking” (and also suggests that Lesslie Newbigin and missiologist Christopher Wright hold similar views). Deciding whether or not he is right to dismiss current understandings of mission, ie as encompassing social welfare, political and cultural transformation, and care for creation on (apparently) the same (and sometimes a higher) level as gospel proclamation and discipleship, is something for another time. But, I think he is correct in his presentation of Paul’s understanding of mission as essentially evangelism, discipleship and church planting. (De Young’s article is fairly brief and worth reading in full.)