Peter Carruthers

Just after Easter, I was asked to give a short talk at a local ‘Rural Churches Fellowship’ lunch. I took as my topic, ‘Jesus in the countryside’. My aim was to tell the story of Jesus’ passion and resurrection from a rural angle, using five works of art that set events of that week in rural settings and which I find particularly inspiring. Some of my content was drawn from two earlier articles (here and here), which explore the themes in greater depth. Here is an edited transcript.

Good news from the countryside

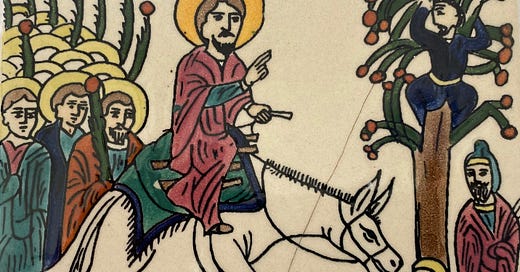

The image above is of an Armenian ceramic tile I bought in Jerusalem in 1979 (sadly it broke and was mended sometime between then and now; hence the crack). It depicts Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on a donkey on ‘Palm Sunday’. It is one of many ‘life of Jesus tiles’, painted by the Karakashian family of Jerusalem Pottery, based on “original artwork from the eighteenth century, from St. James Armenian Cathedral in Jerusalem, and from Greek, Coptic, Assyrian icons and old Christian manuscripts”.

All four gospels recount Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, but from different standpoints.

Matthew, Mark and Luke describe how Jesus’ Palm Sunday journey starts in a rural setting, in the villages of Bethany and Bethphage on the Mount of Olives, and proceeds through fields and olive groves down the side of the hill to enter the city from the east side.

John tells the story from an urban viewpoint, following the crowd of city people that, hearing of His approach, come out of Jerusalem ascending the hill to greet Him with palm branches and hosannas.

The King, bringing the hope of peace and salvation, comes from the countryside to the city and His ‘rural’ followers are surprised by the ‘urban’ people’s response! Good news comes from the countryside!

The cross in the countryside

Although I have not seen the original of Paul Gaugin’s, The Yellow Christ, above, I have seen the crucifix that inspired it, and was myself inspired by the combination of the crucifix, its setting and the painting.

The crucifix is in the 16C Chapelle de Notre-Dame de Trémalo, near Pont-Aven in Brittany.

Pont-Aven was a centre for many artists and Gaugin spent time there in the 1880s and 1890s, before ending up in Tahiti, where he painted what became perhaps his more famous works.

The chapel is on a hill above the town in quiet countryside surrounded by woods and fields. It is a peaceful, idyllic place. Inside, on the wall, is the simple carved wooden crucifix that became the centrepiece of the painting.

Gaugin situates the crucifixion in a rural setting. Jesus is on the cross in the Breton countryside; the women around the cross are Breton peasant women.1

Whatever Gaugin intended, for me, the scene conveys a sense of peace. Jesus has died, yet His death brings peace and hope to the countryside. He has suffered terrible pain and humiliation, but He is lifted up and enthroned over people and all creation.

Resurrection appearances

The Gospels describe or refer to eight of Jesus’ appearances after His resurrection. Five occur in rural locations. Food, the produce of farming or fishing, features in three.

The three most detailed accounts, especially, teach us much about the implications of Jesus’ resurrection for ‘countryside’ and ‘creation’.

Supposing him to be the gardener

Noli me tangere is one of a series of frescoes by Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro, 1395-1455), and his co-workers, in the cells and corridors of the Convento di San Marco (now a museum) in Florence, Italy. I came across a photo of this particular fresco some years ago and used it many presentations on environmental theology. I was, therefore, very pleased to see the original when I visited the museum in 2014.

Mark reports simply that when Jesus rose “he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast seven demons” (Mark 16:9). John provides more detail of Mary’s meeting with the risen Jesus in the garden (John 20:1-18).

It is significant that this first appearance took place in a garden, that it was to a woman, and that she mistook him for the gardener.

The garden evokes Eden, the place of fellowship between God and Man and cooperation in tending and caring for creation. Jesus, who is Lord and God, coming walking in the garden recapitulates the Lord God in Eden. Fellowship and cooperation are restored.

He comes first to Mary Magdalene. She represents Eve. Eve succumbed to temptation first, so she, her ‘successor’, is the first to be restored.

It is fitting also that she mistakes Him for the gardener. For He is! In his depiction of this encounter, to emphasise this, the 15C painter Fra Angelico painted Jesus with a hoe (see above).

The Road to Emmaus

Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus has also provided an illustration in many presentations on environmental theology, and I have, of course, seen the original in the National Gallery.

Later on Resurrection day, Jesus appears to two disciples’ on a country road to the village of Emmaus. Like Mary Magdalene, they do not, at first, recognise Him. In her case, all that was needed was for Jesus to speak her name. For Cleopas and companion (perhaps his wife), recognition only came when Jesus around the meal table “took the bread, blessed and broke it and gave it them” (Luke 24:13-35).

Just as in the meeting of Jesus and Mary in the garden, there are echoes of Eden in the Emmaus story. As Adam and Eve’s eyes were opened, so were the eyes of the two opened – not to guilt and shame, but to the One who had redeemed what the first man and woman lost and who makes all things new.

As one whose lifelong career has been, in different ways, concerned with countryside and farming, I see Jesus walking through the fields, flocks and forests of the Judean countryside, silently declaring the message of redemption, now made possible by His death and resurrection, to the countryside, to our villages and hamlets, and to a creation waiting “with eager longing”.

But the main message for the countryside and creation in the Emmaus account is found in the matter of ‘continuity and transformation’. As Paul explains, His continuous yet transformed body is a foretaste of our own resurrection and that of the whole cosmos.

By the lakeside

The third appearance takes us back to the Sea of Galilee. It is the second miraculous draft of fish recorded in the Gospels. Both took place after a fruitless night’s fishing. Both were defining moments for Simon Peter. The first (Luke 5:1-11) preceded his call, the second his re-instatement. But there was a particular difference. On the post-Resurrection occasion, the nets did not break.

Fish of course evoke ‘fishers of men’. The catching of 153 big fish both enacts the Great Commission, and promises its outcome. Commentators have made much of the 153, including suggesting it connotes all the nations of the world.

But it also speaks of the countryside and creation. Like the feeding of the four and five thousand, the catch promises and “foreshadows the flowering of God’s creatures in God’s kingdom”,2 the super-abundance that will mark the time “when’, as Amos ends, “the ploughman shall overtake the reaper and the treader of grapes him who sows the seed; the mountains shall drip sweet wine, and all the hills shall flow with it”, when, in William Dix’s words based on Psalm 65, “Bright robes of gold the fields adorn, the hills with joy are ringing, The valleys stand so thick with corn that even they are singing”.

Gaugin painted several crucifixions set in the Breton countryside, for example, The Green Christ, which combines images from several locations in the Breton countryside and coast.

Echlin, E P. 2004. The Cosmic Circle, p 98. Dublin: The Columba Press.

An excellent piece, Peter! I love the paintings and artefacts that you have used to illustrate your theme. It is a reminder that we will never save the planet; yes, we can look after it, but we long for it's complete redemption.