Peter Carruthers

This is the second of my promised follow-up articles to my review of Rod Dreher’s ‘Benedict Option’ (‘Benedict’) and ‘Live not by Lies’ (‘Lies’). The first is here.

Both books address the issues of how to be church in a time of crisis. How, asks Dreher, do we remain faithful followers of Christ in a hostile post-Christian and increasingly anti-Christian society? How do we practise faith, preach the Gospel, and care for the needy when in ‘exile’ and remain righteous when the ‘foundations are destroyed’? How do we ‘survive the flood’ and ‘weather the storm’ that have come, and are coming with even greater intensity, upon us?

The Great Flood

In ‘Benedict’, Dreher likens our situation in western society to the Great Flood that engulfed his home state of Louisiana in August 2016. The flood was a ‘thousand-year weather event’ and no one in recorded history had ever seen that land inundated. No one expected it. Few were prepared. Many lost everything.

“We Christians in the West”, he writes, “are facing our own thousand-year flood - or, if you believe Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, a fifteen-hundred-year flood: in 2012, the then-pontiff said that the spiritual crisis overtaking the West is the most serious since the fall of the Roman Empire near the end of the fifth century. The light of Christianity is flickering out all over the West…. This may not be the end of the world, but it is the end of a world, and only the wilfully blind would deny it. For a long time we have downplayed or ignored the signs. Now the floodwaters are upon us -and we are not ready.”1

‘Benedict’ is predicated on the proposal that, just as Benedict of Nursia was raised up to enable the church (and arguably western civilisation) to come through the crisis following the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, so Benedict’s example, rule, and modern emulators and interpreters, offer a way to be church and remain faithful in our present cataclysm. “Christians besieged by the raging floodwaters of modernity await someone like Benedict to build arks capable of carrying them and the living faith across the sea of crisis”.2 The Rule of St Benedict, Dreher contends, provides a simple and solid framework for these ‘arks’.

The Rule is a set of practical instructions as to how to organise and govern the common life of a monastic community. To the (already) traditional vows of poverty and chastity, Benedict added “three distinct vows: obedience, stability (fidelity to same monastic community until death) and conversion of life, which means dedicating oneself to the lifelong work of deepening repentance”.3 At its heart, the Rule’s aim is to equip the disciple to “enter upon the service of thy true king, Christ the Lord”. As Esther de Waal wrote, “if there is any one thing that is characteristic of Benedict, it is that he makes the love of Christ the focal point to which everything must lead”.4

Although the Rule was written for monastics, Dreher contends that its principles of order and stability, prayer and work, asceticism and balance, community and hospitality provide a sound basis for ordering the common life of all orthodox Christians seeking to “live and witness faithfully as a minority in a culture in which we were once the majority”. Much of ‘Benedict’ is a treatise on how these principles can shape Christians’ relationships with God, one another and with state, society and culture.

A gathering storm

In ‘Lies’, Dreher likens our present situation to a ‘gathering storm’. Even in the few years between the publication of ‘Benedict’ (2017) and ‘Lies’ (2020), the crisis deepened and hostility to Christianity heightened, Dreher believes, and ‘Lies’ has a much darker and more urgent tone than ‘Benedict’. The storm “is coming, and it is coming fast”.

“In the West today, we are living under decadent, pre-totalitarian conditions. Social atomisation, widespread loneliness, the rise of ideology, widespread loss of faith in institutions, and other factors leave society vulnerable to the totalitarian temptation to which both Russia and Germany succumbed in the previous century”.5

“Lies’ draws on the example of the dissidents of the Soviet era in Eastern Europe to set out how we can create “shelters from the gathering storm”. In ‘soft totalitarianism’, Dreher argues, Christians need to ‘value nothing but truth’, ‘cultivate cultural memory’, strengthen family, church and community, and especially, be prepared to embrace the ‘gift of suffering’ (and he devotes a chapter to each of these themes).

The gates of hell

Both ‘Benedict’ and ‘Lies’ urge us to reconsider and ‘reconfigure’ church, so as to create these ‘arks’ and ‘shelters’. Neither advocates tearing it all down and starting again - as if we could, or should try to, anyway. Rather, both point us to the past, to our God-given roots and foundations, to scripture and tradition, and to the example of saints and martyrs, both ancient and modern. They direct us back to the first church, which in the face of a pagan, pluralist and hostile culture, spread like wildfire, grew exponentially, and turned the world upside down. And, ultimately, they remind us that it is the Lord Jesus, not us, who builds the (one) Church, ‘against which the gates of hell cannot prevail' (Matthew 16:18).

What exactly Jesus meant by, “I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18), has been much debated.

‘Gates’ are where city authorities convened (Proverbs 31:23) and are suggestive of the (demonic) powers of hell (Ephesians 6:12) that are ranged and are raging against the Church, “against the Lord and His anointed” (Psalm 2:1-3). And, as Western society ‘re-paganises’, it seems these powers are in ascendancy.

In his 2022 ‘The Return Of The Gods’, Messianic Jewish rabbi, Jonathan Cahn, “puts forward the thesis that ancient Near Eastern gods like Moloch, Asherah, Baal, and others, to whom humans were sacrificed, did not go away (because they are demons, not mere fictions), but were suppressed by Judaism and then the spread of Christianity. Yet as Christianity declines in the West, says Cahn, we are seeing these ancient gods return. He means it literally”.6

Inspired by Cahn’s book, Jewish writer, Naomi Wolf, observed:

“I think it is possible that for four thousand plus years — and then for two thousand — God’s covenant has in fact largely protected the West, and that we have had His blessing for so long that we have taken it for granted; and that in the last few years, we have released our hold of God’s covenant – and that God has simply, as He warned us in the Old Testament that he could — withdrawn; and left us to our own devices — so we can see for ourselves how we will do when we depend on humans alone. In the absence of God’s covenant and protection in the West, great evil is flourishing.”

Michael Heiser offers a somewhat different (although, I would argue, a complementary, not a contradictory) perspective on Jesus’ words.

“The rock which Jesus referred to in this passage was neither Peter nor Himself; it was the rock on which they were standing—the foot of Mount Hermon, the demonic headquarters of the Old Testament and the Greek world.

“We often presume that the phrase ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it’ describes a Church taking on the onslaught of evil. But the word “against” is not present in the Greek. Translating the phrase without it gives it a completely different connotation: ‘the gates of hell will not withstand it’.

“It is the Church that Jesus sees as the aggressor. He was declaring war on evil and death. Jesus would build His Church atop the gates of hell—He would bury them.”

Heiser’s perspective here is suggestive of Paul’s words to the Ephesians - “that through the church the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places” (Ephesians 3:10).

In either case, we see a Church needing to ‘reconfigure’ for a level of spiritual warfare hitherto unknown to most of us in the 21C West.

Blitzkrieg

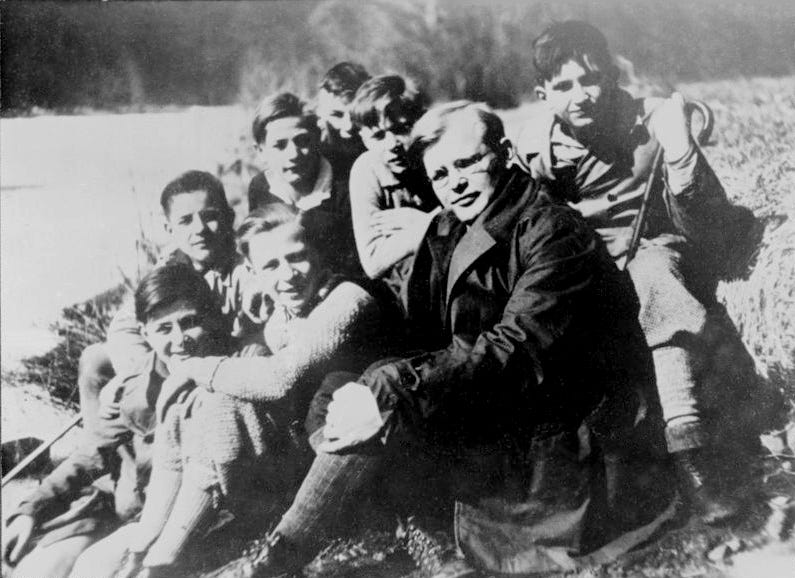

Here, I think Dietrich Bonhoeffer is important. Like St Benedict and the Soviet dissidents, he formed his theology in the midst of, and in response to, a singular crisis - the ‘flood’ and the ‘storm’ of the catastrophic events and the explosion of demonic evil that overwhelmed Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. And, like them, he grappled with the challenge of how Christians and churches relate to a society that is suddenly ‘post-Christian’ and ‘anti-Christian’.

In an article in March this year, Carl Trueman7 described how his friend and colleague, the Roman Catholic writer, Francis Maier, had recently drawn attention to the importance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer for the church in America [and, I would argue, in the UK also] in an article prompted by the 90th anniversary of the Barmen Declaration this year. The Barmen Declaration publicly opposed the ‘German Christians’ who were seeking an accommodation with Nazism. Bonhoeffer was a signatory. Trueman goes on as follows.

“That Maier, a Catholic, calls on Bonhoeffer is a sign of the times. This is not simply because in the current climate Catholics and Protestants share common cultural concerns. It is also because the great temptation of our day, that of conflating politics with Christianity, is intense. The stakes are not as high as they were in Germany in 1934 [we hope!]. But the principal challenge for Christians, that of remaining faithful as witnesses to the gospel rather than enablers of those whose politics resonate with our cultural tastes, is the same.”

As we in the UK head towards a General Election, we might reflect a little more deeply on the challenges implicit in these words.

Bonhoeffer was one of the few who quickly understood even before Hitler came to power that national socialism was a brutal attempt to make history without God and to found it on the strength of man alone. And he resisted the demonic Nazi system to the point of his own death.

Like us now, he struggled with how the church understands itself, and how we live as Christians after Christendom. He saw the need for the church to respond to the crisis, to renegotiate both its relationship with the state and its understanding of what it means to follow Jesus. For a while, he led an ‘underground’ training college for pastors for the ‘Confessing Church’. Out of this experience, he wrote ‘Life Together’, which reveals how much he saw the church as called to be a ‘disciplined community’, a ‘community of love’ (at any time, but even more so in the midst of crisis).

Bonhoeffer saw the dire state of the church of his own time and how ill-equipped it was to respond the the crisis. In The Cost of Discipleship, he famously wrote, “cheap grace is the deadly enemy of our church. Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate”.

I wonder what Bonhoeffer would make of much of our church in Britain and the West today? In the decades since WW2, the churches have seen remarkable growth and renewal. Yet they have, it seems, greatly sold out, either to an accommodation and capitulation to the spirit of the age, or to a form of individualistic, emotivist, therapeutic, experience-driven, performance-orientated, pragmatic, neo-gnosticism, with its fads and fixes, and false prophets and false promises. There is much apparent ‘madness’ in all wings and flavours of ’church’ just now. Yet there are still genuine prophetic voices (some quoted here) and many grass-roots faithful. Those who fear the Lord need to speak to each other and the Lord will pay attention (Malachi 3:16).

Although Bonhoeffer worked mostly within the existing institutions his radicalism put him at odds with most of the church establishment, and, of course, with the Nazi state, leading eventually to his execution. Some of his teachings are enigmatic, and evangelicals are uncomfortable with his apparent positions on key doctrinal issues. Nevertheless, Bonhoeffer’s example and his methodology place him, in my view, in the ‘Jeremiah tradition’ – a prophet seeking to make ‘theological sense out of a political crisis’. Along with St Benedict and the Soviet dissidents, he urges us to embrace costly discipleship and radical community. His words and example help us to build the ‘arks’ and ‘shelters’ to enable us to survive the flood and weather the storm that has come and is coming upon on us. Bonhoeffer shows us how to ‘be church in crisis’.

A good 25-minute video introduction to Bonhoeffer is here.

’Agent of Grace’, a film about Bonhoeffer’s life, is here.

Dreher, Rod (2017). The Benedict Option, Sentinel, New York, p 8.

Dreher (2017), op cit, p 18.

Dreher (2017), op cit, pp 50-51.

de Waal, Esther (1997), Living With Contradiction, Canterbury Press, Norwich, p 30.

Dreher, Rod (2020), Live not by lies. Sentinel, New York, p 93.

Carl Trueman is a professor of biblical and religious studies at Grove City College and a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.